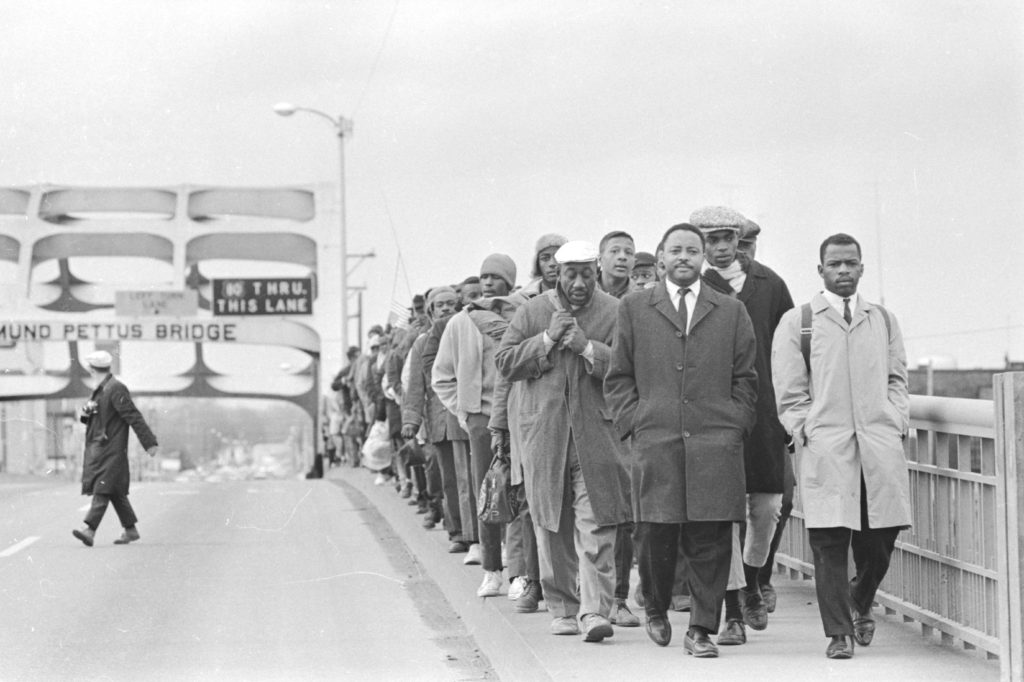

We all know of the March on Washington, culminating in Dr. Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial before 250,000 people filling the National Mall. It’s one of the most iconic and important moments in American history. Rustin introduces many folks to the overlooked greatness of Bayard Rustin (Colan Domingo), the organizer of the event.

Bayard Rustin was an important civil rights leader who was relegated to the background of the movement, and sometimes even ostracized, because he was a gay man. In the 1950s and 1960s, being a former Communist didn’t help, either.

Rustin’s mentor A. Philip Randolph (played in Rustin by Glynn Turman) is the other most overlooked male civil rights leader. Randolph’s two greatest accomplishments, the integration of the military and of the defense industries, occurred before television (and were filtered by the white mainstream print media). A personal note from The Movie Gourmet: my decades-long career has been in politics, and one of my very first political day jobs was funded by the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Here is more on Randolph and Rustin from the APRI website.

Rustin takes us behind the scenes, and we see the strategic disagreements, petty jealousies and jockeying for status between civil rights leaders. It’s important that the leaders came from generational strata. In 1963, Randolph was 74. Rustin was 52. NAACP head Roy Wilkins was 61, and Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell was 55, both at the peaks of their careers. MLK was a rising superstar, but still only 34. John Lewis was still only 23.

In birthing the March on Washington, Rustin was fighting the overt attacks of J. Edgar Hoover and Strom Thurmond and the covert obstructionism of Attorney General Bobby Kennedy. Rustin also had the contend with the antagonism of Wilkins and Powell. But, Rustin had two cards to play – the respect demanded by Randolph and the rock star sizzle of MLK.

In a stellar, commanding performance, Colman Domingo is charismatic as Rustin. Domingo has been so good in everything I’ve seen him in: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Zola, Selma and Lincoln. Glynn Turman brings gravitas and moral authority to Randolph. In ingenious, against-type casting, Chris Rock is excellent as the funny-as-a-heart-attack Roy Wilkins. Jeffrey Wright PERFECTLY captures Adam Clayton Powell.

Ami Ameen has the challenge of satisfying audience expectation in portraying MLK. He gets the speech patterns and mannerisms right, while inhabiting a still-young MLK growing into the leader he was just becoming.

If you want to learn more of Bayard Rustin, I recommend Matt Wolf’s award-winning, but hard to find, short doc Bayard & Me, which features Rustin’s longtime partner Walter Neagle’s recollection of his life with Rustin; it’s an important insight into both Civil Rights and LGBTQ history.

Rustin was directed by George C. Wolfe, whose previous feature, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, was my #2 movie of 2021. We need to see more movies from this guy.

Rustin is now streaming on Netflix.