The Last Full Measure tells the true story of a slain military hero who, due to the efforts of those who survived the battle, finally get a deserved Congressional Medal of Honor decades after his death. It’s a pedestrian movie periodically enlivened by excellent supporting performances.

The Last Full Measure is set in 2000, 32 years after the battle, when a selfish Pentagon career-climber (Sebastian Stan) is stuck with the unwanted assignment of validating the act of valor (it ain’t going to help him advance his career). He bitterly visits geezer after geezer to find out why the medal is deserved and why it wasn’t awarded earlier.

I’m not convinced that Sebastian Stan brings anything to non-action movies, and his parts of the film drag (which is bad, because he’s the main character).

Remarkably, the supporting cast of William Hurt, Christopher Plummer, Diane Ladd, Samuel L. Jackson, Amy Madigan, Peter Fonda and Ed Harris have combined for two acting Oscars and sixteen nominations. Christopher Plummer ia absolutrly radiant here; it’s some of his best work. Peter Fonda, in his final movie, also gives an indelible performance. Amy Madigan’s part is perfect matched to Madigan’s piercing eyes. And every Social Security-eligible actor is very, very good.

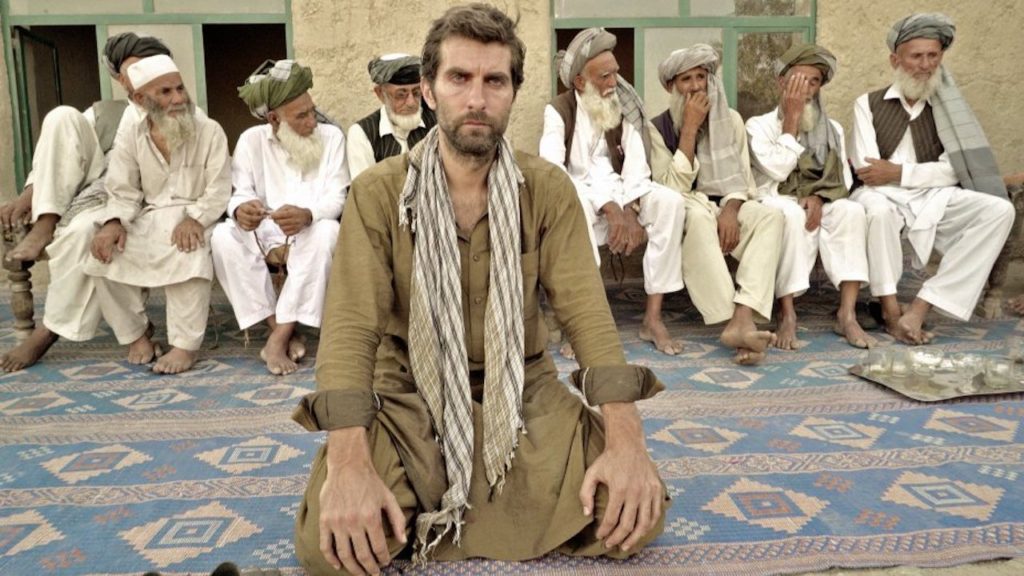

The battle scenes in the flashback are well-crafted, and Jeremy Irvine is very good as the hero. But this won’t make any list of top 20 Vietnam War films.

If you must watch The Last Full Measure, which is available on most of the streaming platforms, just fast forward until you see somebody old.