In Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), Questlove recovers the never-before-seen film of the Harlem Cultural Festival over six weekends in 1969. The promoters had tried to market the footage as “the Black Woodstock”, but had no takers at the time (for the obvious reason).

This is a superb concert film, but that’s not all it is. 1969 was an important historical and cultural moment – especially for American Blacks, and Questlove supplies the context. A 2021 audience cannot miss the parallels between 1969’s Black Is Beautiful and Black Power and today’s Black Lives/Black Voices.

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson is widely-known as drummer of The Roots and bandleader for The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon. Creative and versatile, he is Emmy-nominated and Grammy-winning, he is going to win an Oscar for this, his directorial debut for a feature film. Summer of Soul proves that Questlove is such a gifted storyteller that I hope he takes on narrative fictional filmmaking, too.

The music in Summer of Soul is fantastic:

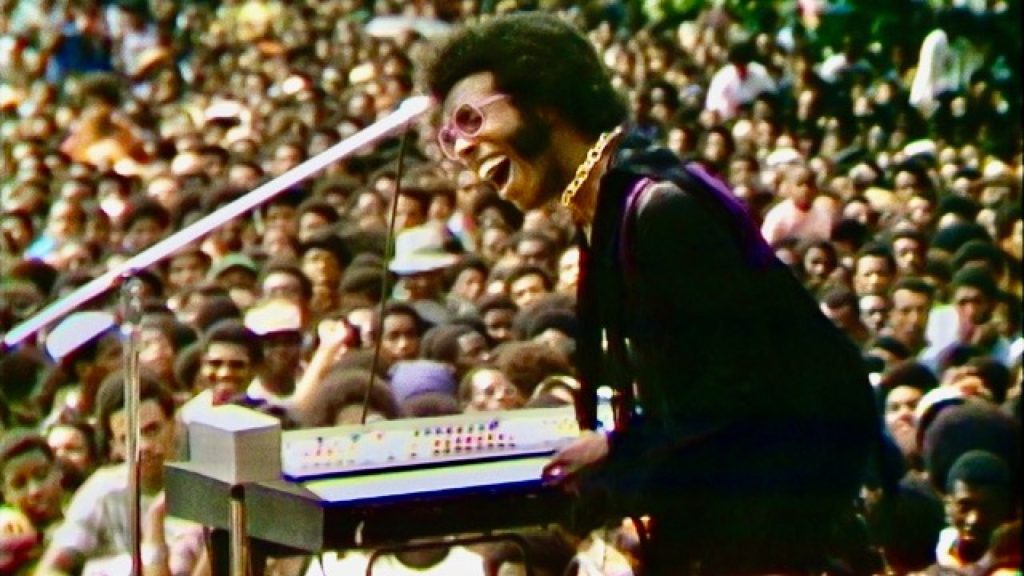

- Sly and the Family Stone shattered expectations with their garb, racially integrated band and female musicians on trumpet and keyboards. Their psychedelic funk and super-charged ebullience blew away the audience. (BTW Vallejo native Sly Stone is now age 78.)

- Stevie Wonder was only 19, 3 years before Superstition, and already taking his remarkable creativity and musicianship down new roads.

- Gladys Knight and the Pips – watch the Pips and appreciate how those guys really worked it.

- BB King at the height of his popular breakthrough, singing Why I Sing the Blues.

- The Fifth Dimension were best sellers among the white mainstream – and here they were finally accepted by a Black audience. Billy Davis Jr. and Miriam McCoo get to relive the experience on camera in one of Summer of Soul’s most touching moments.

The musical high point is a rendition of Precious Lord, Take My Hand by Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples. Mahalia was then 58 and a legend, and this was her signature song. Mavis was already a showbiz veteran at 30 and at the top of her game. The Reverend Jesse Jackson introduces the song with a heartbreaking account of Martin Luther King asking for this, his favorite hymn, seconds before his murder. Mahalia was not feeling well, and asked Mavis to kick off the song. Mavis’ first verse is volcanic, then Mahalia takes over and the two finish together in an explosion of emotions. Epic.

Something else happened that summer – the manifestation of JFK’s pledge to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth. Questlove uses file footage of person-on-the-street interviews to contrast the reactions of Blacks and Whites. It’s a Rorschach test of privilege and alienation.

Gladys Knight recounts “it wasn’t just about the music”. BB King performed here just weeks after the release of The Thrill Is Gone, and he must have included Thrill in his set, but I’m sure that Questlove instead chose Why I’m Singing the Blues to focus on that song’s larger subtext for Black Americans.

And the need to show the militant commitment to self-determination must be why Questlove features so much of Nina Simone at her rawest. If she had ever worried about being too harsh, Simone was well past that point in 1969.

On a lighter note, ironic sombrero-wearing must have been a thing in Harlem that summer – check out the crowd shots (and drink a shot for every sombrero.)

Summer of Soul etc. etc. has also earned the #13 ranking on my list of Longest Movie Titles.

How good is Summer of Soul, which swept the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at Sundance? It’s hard to imagine it not winning the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, and I’m guessing it will be that rare doc nominated for Best Picture. FWIW I’m putting it on my list of Best Movies of 2021 – So Far.

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is in theaters and streaming on Hulu. It’s worth watching for the music and worth it for the history, too; for the combination, it’s a Must See.