This week: Not one, but TWO Watch At Home film festivals.

The Mill Valley Film Festival is always the best opportunity for Bay Area film goers to catch an early look at the Big Movies – the prestige films that will be released during Award Season. This year is the same – except we don’t even have to visit Marin County in person. Watch at home.

Cinejoy is Cinequest’s October virtual fest. More watch at home choices, especially focused on indie gems that you can’t see anywhere else.

ON VIDEO

Stuntwomen: The Untold Hollywood Story: “Actresses play characters, but stuntwoman play actresses playing characters, while driving fast and kicking ass.” Streaming on iTunes and Google Play.

The most eclectic watch-at-home recommendations you’ll find ANYWHERE:

- Sibyl: trashy, but in that sly and expert French way.

- #Alive: A Korean Home Alone with zombies.

- Rodents of Unusual Size: 5 million orange-toothed critters and a Cajun octogenarian.

- I Don’t Feel at Home in this World Anymore: schlub goes postal.

- The August Virgin: searching for reinvention. Best Movies of 2020 – So Far.

- Apocalypse ’45: I never imagined hell being that bad

- Coup 53: uncovering what we suspected

- An Easy Girl: summer school in Cannes

- Moka: whodunit mixed with psychological thriller

- Lucky Grandma: tour de grouch

- She Dies Tomorrow: you have not seen this before

- Prime Suspect: binging one of TV’s greatest episodic characters.

- The Speed Cubers: odd, and then profound

- Gordon Lightfoot: If You Could Read My Mind: no, I hadn’t thought of him for decades, either

- Yes, God, Yes: learning that hypocrisy is a choice.

- Dateline-Saigon: the truth will out

- The 11th Green: a thinking person’s conspiracy

- Driveways: I can’t think of a more authentic movie about intergenerational relationships than this charming, character-driven indie. Best Movies of 2020 – So Far.

- The Lovebirds: A rom com with a playful plot and a truthful relationship.

ON TV

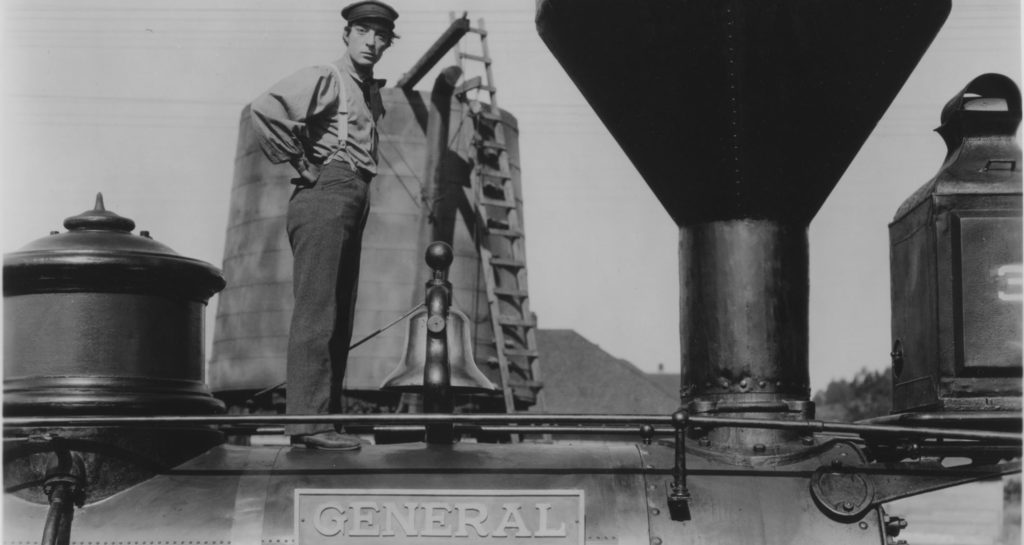

On October 4, Turner Classic Movies presents an afternoon and evening of Buster Keaton that is one of the best programs that TCM has ever curated. First, there’s Peter Bogdanovich’s fine 2018 biodoc of Keaton, The Great Buster: A Celebration. I had thought that I had a good handle on Keaton’s body of work, but The Great Buster is essential to understanding it.

TCM follows with four movies from Keaton’s masterpiece period: Sherlock, Jr. (1924), The General (1926), Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) and Seven Chances (1925). After 1928, Keaton’s new studio took away his creative control, and his career (and personal life) crashed.

This is a chance to appreciate Keaton’s greatest work. I just wrote about Steamboat Bill, Jr. for last year’s Cinequest. I’ve also recommended Seven Chances for its phenomenal chase scene, one that still (ninety-five years later!) rates with the very best in cinema history.